I, unpopularly, love rodents. There are pictures of me as an infant with Munchkin, our first of three rabbits, with her paws up on my rocker. In fourth grade, my friend Crystalin and I started a club called Starrats (a clever palindrome, if you’re eight) where we played intergalactic rats named (perhaps less cleverly) Mouse and Cheez. I had a Stuart Little themed birthday as a child and a “rat girl summer” themed birthday for my 28th. So how did I end up in the strange position of trapping rodents as a job?

The answer is location, location, location! While rodents may be considered pests all over the world, they are pests to a different degree in New Zealand as invasive species that threaten the incredibly unique flora and fauna that live here. When we moved to Akaroa, we knew there was some pretty amazing wildlife on the peninsula, from the world’s smallest dolphins to the littlest blue penguins (kororā). Wanting to get involved locally and have an outlet outside of our restaurant jobs, we reached out to the local penguin conservation organization to see if they had any opportunities. They invited us to volunteer with their scientist on a penguin monitoring run to collect data on the health of the colony. Their regular trapper was also on holiday, so they offered us paid positions to do occasional work on the trap lines. Eager to contribute, we hoped we’d be up to the task! But before getting into the specifics of our work, I’ll briefly explain why trapping is so important.

An Abbreviated Natural History of New Zealand1

Before separating into the landmasses we know today, the continents were once connected as supercontinents. The supercontinent Gondwana consisted of the geographic areas that now belong to the Southern Hemisphere: South America, Africa, Antarctica, Australia, and Zealandia, plus the Arabian and Indian subcontinents. Gondwana also combined with Laurasia to form the more commonly known supercontinent Pangaea. About 85 million years ago, New Zealand began to split off, eventually forming the Tasman Sea that now separates it from Australia.

So for 85 million years, New Zealand developed in relative isolation to the rest of the world, splitting off before the development of marsupials, mammals, and other creatures like snakes.2 In fact, the only native mammals here are bats and marine mammals. Sometimes you have to remind yourself that there are no human predators here — no lions, tigers, or bears (oh my)! On a camping trip our first month here, our hearts pounded as we woke up to loud rustling near our tent followed by otherworldly screeching noises that went on for hours. I slept with one eye open before learning the next day that those horrible sounds come from an invasive species — possums!

Furthermore, other continents have histories of human habitation going back at least 10,000 years. In New Zealand, evidence suggests human settlement began only 800 years ago. Without mammals, creatures like flightless birds (such as the kiwi bird, New Zealand’s national icon) and the largest insects on earth (the size of a GERBIL) could evolve. There are an estimated 80,000 species endemic to New Zealand, meaning they are found here and nowhere else in the world. In comparison, the UK only has two endemic species.

Species that went extinct on other continents more than 100 million years ago survived, with some of these prehistoric creatures still existing in New Zealand.

For every species still existing in New Zealand, there are dozens that have gone extinct. While some theories suggest extinctions as a result of volcanic eruption or earlier human contact, the vast majority of extinctions were caused by human settlement. By 1770, around half of New Zealand’s bird species were already extinct due to the introduction of Polynesian rats and dogs, as well as hunting and habitat destruction by the Māori. The prehistoric moa (flightless birds up to 12 feet tall and 500 pounds) were still around at the time of first human settlement, but were hunted to extinction within about 100 years.

The arrival of Europeans dramatically accelerated the decline and extinction of native species, with the ecological changes in New Zealand in just a hundred years being comparable to the changes that happened in Europe over 2,000 years. The British imagined New Zealand as a new and better Britain, preserving the best of European civilization while avoiding its problems. Of course, this vision came at a significant cost for the Māori inhabitants of the land, primarily via numerous conflicts and questionable translation practices on land treaties that amounted to stealing. The colonizers also brought disease and weapons that harmed existing populations. As for the natural environment, they directly killed animals they believed were a threat to their lifestyle. For example, for almost a hundred years, the government offered a cash reward for killing kea, the world’s only alpine parrot, because they were believed to attack sheep. Aside from the rats that stowed away on their ships, they also brought creatures intended to make this new land feel like home: rabbits, hedgehogs, possums, and stoats.

And that’s how we get back to rodents. These rodents (and the humans who brought them here) are directly responsible for the endangerment and extinction of countless native New Zealand plants and animals. Their continued presence is a thorn in the side of conservationists. As of 2023, more than 75% of native reptile, bird, bat, and freshwater fish species in New Zealand were at risk of extinction. Introduced predators threaten native species directly by eating birds, their chicks, or their eggs. They also compete with native species for food sources, and contribute to habitat loss through grazing. Mammals like rabbits and wallabies eat through native bush, preventing its regeneration. And unlike in other countries, these mammals have no predators themselves, allowing their population to grow uncontrolled. While extinction is sad in its own right for the intrinsic value of biodiversity, it is also both a result and an indicator of an ecosystem in crisis. Loss of animal life can lead to associated loss of plant life, as berries and seeds are no longer dispersed by those birds. We rely on plants and trees for clean air and protection from weather crises like floods. Soil, an essential resource for growing food, depends on microbes from other species. Species extinction, particularly at its present rate, can have cascading effects that threaten all life on the planet.

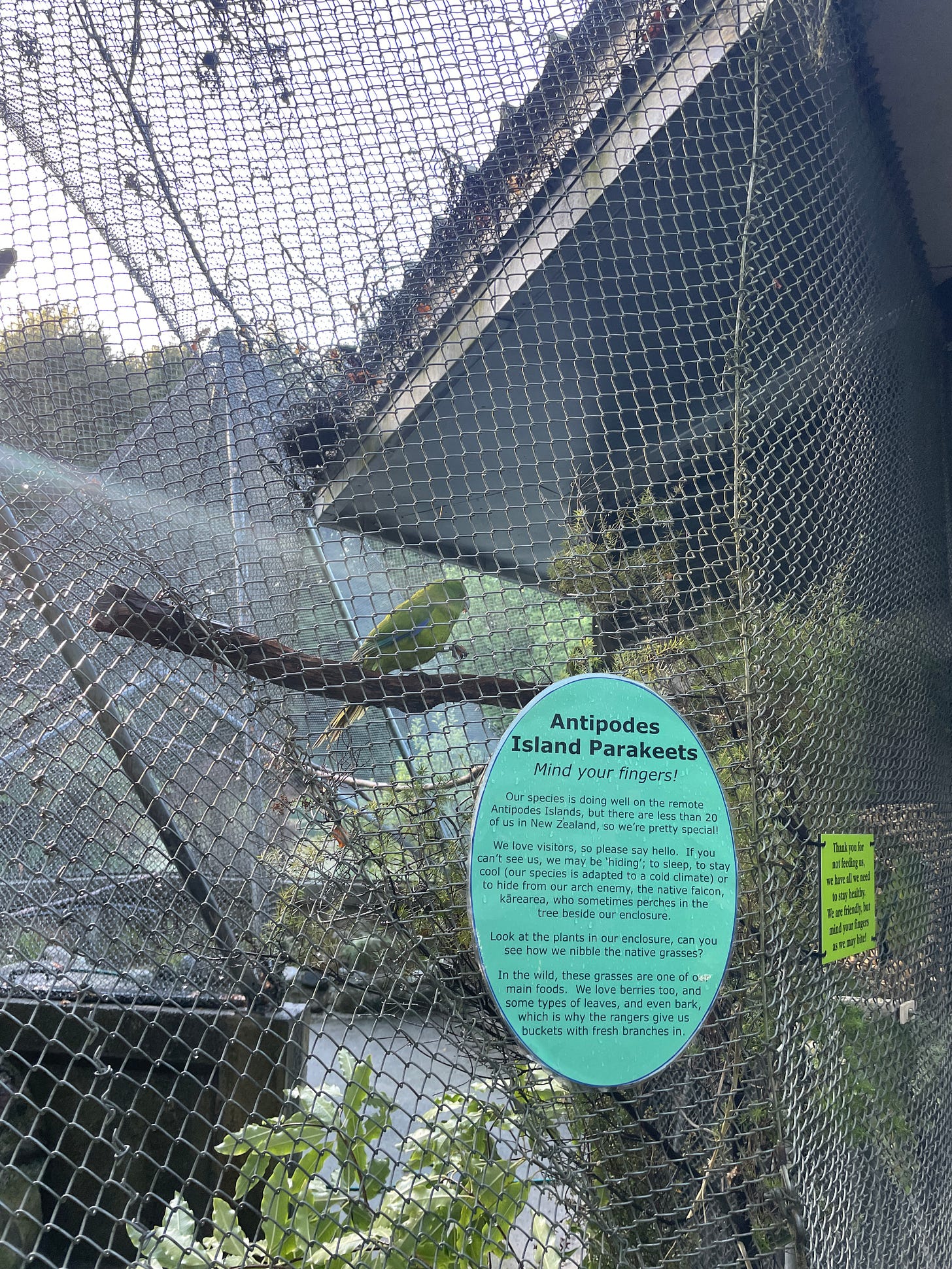

So when the New Zealand government aims to be predator-free by 2050, it’s because native species did not evolve to be able to protect themselves from predators that weren’t around for the vast majority of their existence! And the loss of these species is a threat to the entire ecosystem. Thankfully, there are many success stories! Tiritiri Matangi is an island about an hour away from Auckland. It is an internationally renowned native forest regeneration project and bird sanctuary. Declared pest-free in 1993, native birds can live and thrive here, grow their populations, and eventually be re-introduced to other parts of the mainland where predators have been limited. We are spending a week as volunteers there in July! Near Wellington, community-led, volunteer trapping efforts made it safe to re-introduce kiwis at a local forest park. On the remote Antipodes Islands, the “million dollar mouse" initiative eliminated 200,000 mice. This effort allows unique species of seabirds, landbirds, insects, and plants to survive and thrive.

One of the primary ways to make these success stories happen is trapping. One of the first things we noticed upon moving to New Zealand was the presence of traps on nearly every trail and public space. Our friends even mentioned they volunteered at a regional trap library where residents can borrow traps for their properties. Participating in the penguin monitoring run around the same time we started trapping also really helped bring perspective to why we were doing this work.

Tales of a Trapper

So that’s where our jobs come in! Each day of work, we hopped in one of the big passenger vans with tour groups or staff for a 40-minute ride over the gravel roads to Pohatu/Flea Bay. The land has been a working farm since the 1800s, and the current family who owns and lives on the land has placed legal covenants to protect it in perpetuity. Depending on which trap line we were doing that day, we’d be dropped off somewhere on the 1000 acre property. The land is steep, with rolling hills that really do remind you of Lord of the Rings. About 60% is used for sheep farming, and 40% for native forest regeneration. As you drive or hike down the hills, a beautiful bay with blue water juts out, with just a few properties on the land for the family and a small amount of overnight visitors.

Our supplies for trapping included fresh bait (like rabbit or fish), a knife to cut it up (sometimes the bait was more… identifiable than we would like), gloves, a screwdriver to open certain traps, a yardstick to spring the traps if needed, and a phone to use the TrapNZ app. TrapNZ is the mapping tool used nationwide by the Predator Free 2050 movement to collect data on these efforts. The app showed us the location of the traps and the last time they had been checked.

The majority of our time trapping was spent hiking! The trap lines are usually several miles long, with most traps a few hundred meters apart from one another. As new trappers, we also had to find the traps, which are often tucked away from walking areas. For our first shift, we had a paper list of the traps with little clues (“5 meters left of the large bridge”), which really made it feel like a quest. In some cases, we were hiking on traditional trails, but in others we were walking on sheep tracks or just bush-whacking.

Once we found a trap, we opened it up to check if there was anything inside. The organization uses Department of Conservation-approved humane traps that are essentially giant mousetraps. If nothing had been trapped, we would usually just add fresh bait. If something had been trapped, we needed to clean out the trap, re-spring it, replace the bait, and document what we caught. It usually took a few hours to complete a full trap line, consisting of about 15-20 traps. Then we’d catch the shuttle back to town, usually wet, worn out, but happy with our work!

Reflections on Eco-Tourism

With New Zealand as a top international tourist destination, it’s impossible to deny the harmful impacts tourism has had on the environment and local populations. Being conscious alone does not mitigate this impact. While living abroad for a year as both participants and workers in the tourist economy, we wanted to contribute positively to the place we are living rather than just consume. We feel really lucky to have lived in a place where great conservation work is happening and that we were able to play a small part in it.

In particular, it was really encouraging to work for an organization that seems to do “eco-tourism” really well. Sometimes it feels like pretty much every outdoor organization wants to claim this term, but providing access to nature or wildlife does not inherently make it eco-friendly, safe, or beneficial. At the conservation organization where we worked, it really felt like their efforts to protect and restore the natural environment come first. Rather than just extracting from the environment for profit, eco-tours are used to support the conservation efforts financially while also promoting education and advocacy. Besides the trapping, they also have restored native habitat for penguins, as well as provided over 250 nesting boxes. They rehabilitate injured or underfed penguins to re-release into the wild. A scientist on staff monitors the population to adapt the conservation work and to connect the efforts to nationwide research on endangered species. And the tourism is controlled. While openly accessible public spaces can be incredible, the fact that the land is isolated and accessible only with a staff member allows the penguin colony to be undisturbed by people and vehicles.

The conservation work was personally encouraging on so many levels – it was really cool to see that there are researchers using some of my professional skills (data, GIS, etc.) who also do fieldwork. While my previous jobs had a broad impact, I often didn’t get to see how the data and recommendations I was providing were being used in support of real-life outcomes. It felt really integrating to be collecting data while trapping or monitoring, discussing the questions the researchers are using this data to answer, and then directly taking part in actions to promote further conservation. This made us really excited to seek out other conservation volunteering and jobs while in New Zealand.

Wrapping Up

And there you have it! I made a very casual New Year’s resolution to learn about local flora and fauna, and now I’ve written almost 3,000 words and feel truly passionate about it! So what’s next? As mentioned in our previous post, we left Akaroa at the end of May to do a bit of traveling in the South Island. After literally not being able to get out of our van due to the power doors locking up in below freezing temperatures, we are hastily migrating like birds back to the North. We have an awkward amount of time between now and our bird sanctuary volunteering — too long to just travel but too short to get a proper job, even a seasonal one. So we are putting out some feelers for fun and meaningful ways to spend the winter! More to come soon on our travels since Akaroa!

No formal citations on my newsletter, but a lot of this information is from the first few chapters of Michael King’s Penguin History of New Zealand, which, strangely, also does not include a lot of citations. I can get away with it as a casual newsletter writer, but a historian shouldn’t! Despite his lack of academic rigor, the accounts still line up with what we’ve read in countless museums and on informational signage during our time here. I’ve added links for other sources where relevant.

This is the commonly accepted narrative. In 2006, bits of fossil were discovered that strongly indicate terrestrial mammals once lived in New Zealand. However, they still would have been extinct for several million years before the arrival of humans.